Happy Holidays! For a 2023 with a transformative public education

December 22, 2022Throughout this year we walked together to strengthen the human rights to education in Latin America and the Caribbean.

There were many issues and actions developed by our network.

This 2023 from CLADE we hope to share with more strength and union the path towards social justice from a public education which has care and transformation as its pillars.

Happy Holidays!

Paulo Freire´s Centenary: his legacy as educator is vital for strengthening Y&AE for democracy

September 1, 2021During September, the Latin American Campaign for the Right to Education (CLADE) developed a campaign through communication, awareness and dialogue activities in order to remember the importance of the legacy of the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire and reaffirm our option and struggle for a liberating education that strengthens democracy and promotes social transformation, towards a more just, equitable, sustainable and peaceful world.

CLADE is a plural network of civil society organizations, with presence in 18 Latin American and Caribbean countries and, from its founding moment, has assumed the thought and pedagogy of Paulo Freire as one of its main principles for the struggle for the human right to education in the region.

Emancipatory education, critical thinking, the transformation of educational environments and relationships into spaces for the collective construction of knowledge, reading of contexts, search for alternatives and transforming actions within the horizon of democracy, have been at the core of CLADE’s strategic work.

Within this framework and having in mind the centenary of Paulo Freire, celebrated on September 19, CLADE, articulated with the Latin American and Caribbean Campaign in Defense of Paulo Freire’s Legacy, organized by the Council for Popular Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (CEAAL), developed a month of communication, awareness and dialogue actions, to recall the importance of Freire’s legacy for the guarantee of an emancipating and critical education, which strengthens democracies in our continent and around the world.

Each week of the month, starting on September 3, CLADE members conducted and disseminated webinars, messages and materials in various formats shared through social media and other channels, as well as interviews and conferences, in order to highlight different concepts related to Freire’s legacy for the realization of an emancipatory and democratic education.

The last week of the campaign, from September 25 to 30, highlighted activities and messages about Freire’s legacy for the guarantee of Youth and Adult Education (Y&AE) as a key fundamental human right to promote sustainable development, human rights and, with them, our democracies.

In this framework, the Platform of Regional Networks for Youth and Adult Education in Latin America and the Caribbean, of which CLADE is a member, together with the Latin American Association of Popular Education and Communication (ALER), CEAAL, the International Federation Fe y Alegría (FIFyA), the Network of Popular Education Among Women in Latin America and the Caribbean (REPEM) and the International Council for Adult Education (ICAE), with the sponsorship of DVV International and Open Society Foundations, held a webinar on September 30, from 17h to 19h (Brazil time, GMT-3), to take up, disseminate and discuss the struggles, demands and proposals of the subjects and activists of Y&AE in Latin America and the Caribbean, on the way to the International Conference on Adult Education (Confintea) VII, which will take place in 2022 in Morocco.

The event, addressed, among other aspects, the importance of Freire’s legacy for the guarantee of Y&AE as a human right, popular and transformative education in the Freirean perspective and the situation of Youth and Adult Education in Latin America and the Caribbean in the context of pandemic.

See below de record of this event in English:

Freire’s contributions to Y&AE: towards sustainable development and social and environmental justice

Inspired by Paulo Freire’s perspectives and teachings, and with Confintea VII on the horizon, members of the Regional Networking Platform for Y&AE in Latin America and the Caribbean advocate for a new Y&AE, which should be popular, free, secular, inclusive, emancipatory and transformative. An education that shouldn’t have colonial, sexist, patriarchal and racist features.

In front of welfare and remedial approach that is usually given to Y&AE, we defend that this educational modality must be of quality, with cultural and social relevance. In front of onslaught of tendencies that attempt to privatize education, the right to Y&AE must be guaranteed free of charge. Their homogenizing vision must be overcome with the conception of Y&AE based on the valuation and exercise of education in its multiple expressions. From this point of view, Y&AE not only has a high educational value, but is also a commitment to the transformation of reality, to the change of social structures. Faced with different forms of discrimination and exclusion of a structural nature, this educational modality must contribute to lay the foundations for our societies, which shouldn´t be colonial, patriarchal and racist.

In times in which the motivations for continuing studies, mainly of people over 15 years of age, have been transformed and go far beyond the fulfillment of academic training needs, the priority of Y&AE should be community, permanent and popular education because it is carried out with and in all areas where human beings develop their activities. Furthermore, it takes community processes as the basis for educational objectives and is committed to the process of popular movements and the overcoming of all forms of oppression. Thus, Y&AE should stop concentrating on formal education and give priority to non-formal and popular education, promoting the social construction of knowledge in communities that foster intercultural, intergenerational and intersectoral encounters.

From this perspective, which is in line with Freire’s thought, the new understandings of Y&AE are based on conceiving human beings as subjects of education capable of producing the urgent and necessary changes for the construction of a more just and sustainable society.

For these reasons, and in compliance with the principles of lifelong education, governments should recognize education throughout life and for the diversity of the population as a human right, guaranteeing its full functioning through public policies, institutions and pertinent resources. Literacy, being the basis for the continuity and completion of studies, mainly of the sectors with higher levels of vulnerability, in current times, requires a broad and diverse vision and educational offer that guarantees the continuity of studies at all levels and areas of the educational systems, overcoming the traditional basic literacy approaches, recognizing learning developed in daily life and developing educational processes from the culture and mother tongue.

On the other hand, assuming the challenges of the current context of multiple crises and the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on the daily life of humanity, we propose to rethink an Y&AE whose principles should be the following: education to create harmonious relationships among human beings, community and mother earth, to enjoy health with integral well-being, and to contribute to develop a resilient society, which preserves the existence of all living beings; a liberating and transforming Y&AE, as part of social and popular movements and as a political-educational strategy and project, in such a way that people and communities become active subjects of the required transformations of the planet; education for the construction of a society free of all kind of discrimination, inequality and exclusion; a community and democratic Y&AE, for coexistence, participatory democracy and socio-community participation; an education based on social justice and political, social, cultural, economic and environmental rights of individuals, peoples and nature.

In other words, we defend an education and Y&AE for the encounter among cultures, that overcomes inequalities derived from colonialism, for intercultural dialogue and revaluation of collective knowledge. Based on Freire’s legacy, the transformative education we need, to build the world we want, is one that guarantees the right to know and the accumulated knowledge of humanity and science, with its use for the benefit of all people, from critical pedagogies and cultural dialogue for global citizenship, the defense of rights, peace, common goods and the care of our common home.

>> Read more in our regional statement towards Confintea VII (available in Spanish).

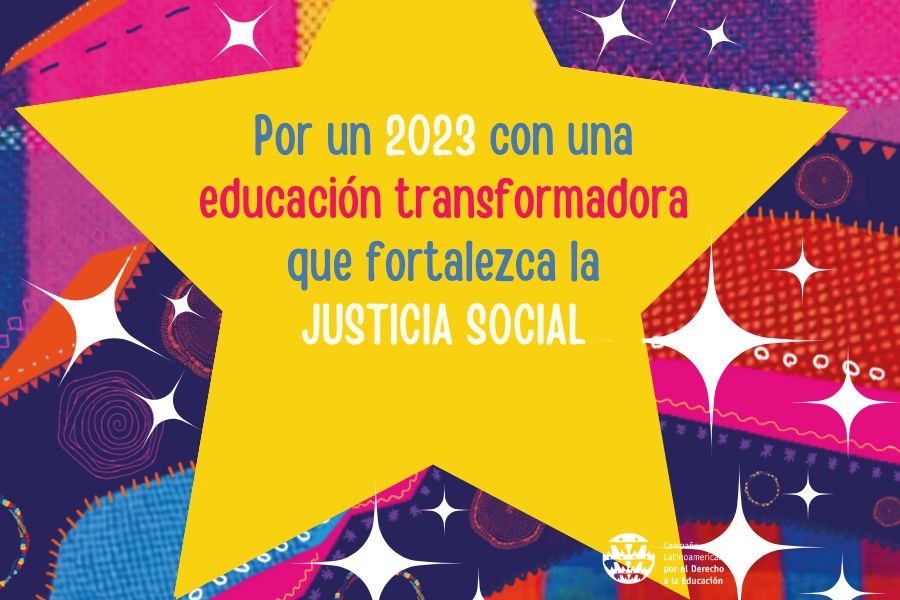

Youth and Adults Education Week will be held from March 22 to 27

March 16, 2021

Stories of students and educators about Youth and Adult Education (ALE), artistic works, live and launching of reports are some of the activities of the Young People and Adults Education Week (ALE Week), which will take place from March 22 to 27.

The initiative is organized by CLADE, in partnership with ICAE, CEAAL, ALER, Fe y Alegría and REPEM, and is carried out within the framework of the Latin American and Caribbean Campaign in Defense of Paulo Freire’s Legacy and the We are ALE Campaign.

See below the activities of the week:

#WeAreALE

On March 22, civil society organizations and networks from around the world will launch the Global Campaign “We are ALE”, aimed at advancing and promoting the concept and practice of youth and adult learning and education (ALE).

The idea of the initiative is to bring together civil society organizations to adopt a shared global definition of ALE. Practitioners, students and civil society representatives from five continents will speak with one voice proclaiming: we are ALE!

The opening event, a webinar on March 22 from 10 a.m. (Brazil time), will be the start of a five-year global campaign to raise the visibility of adult learning and education around the world, and to stimulate civil society to speak with one voice to promote the rights of all young people and adults to quality and lifelong education.

Registration for the March 22nd event

Studies on ALE: financing and migration

March 23 and 25 are the days dedicated to the launching of two studies on Youth and Adult Education, elaborated by CLADE with the support of DVV International. The first report to be launched on March 23rd highlights some of the main features of the financing of ALE in Latin America and the Caribbean, in preparation for the next International Conference on Adult Education (CONFINTEA VII) to be held in 2021; and the other, to be launched on March 25th, presents the situation and challenges of ALE and migration in the region.

The studies will be available on the CLADE website.

Live #ContraVientoyMarea

On Wednesday (24/3), at 4 pm (Brazilian time), it will be the time to talk about the Campaign “Against Wind and Tide” (Contra Viento y Marea, in Spanish). The initiative broadcasts educational and communicative radio testimonies from inspiring experiences of teachers and students of ALE in Peru, Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela in the context of the pandemic.

It has 20 educational and communicative productions that relate experiences, fears and joys of being able to study beyond the difficulties in different countries of the region.

The purpose of this project is to value the ALE and contribute to educational inclusion in Latin America and the Caribbean. The live will be done through CLADE’s Instagram: @red.clade

In addition, during the Week (March 22-26), every day some of the radio testimonies of #ContraVientoyMarea will be broadcasted through CLADE’s social media (FB, TW and Instagram) and the channels of other regional networks allied in the initiative of the Week.

Learn more about #ContraVientoyMarea

Radio program “Claro y Raspao”

On March 24, at 17:00 (Brazilian time), the radio program “Claro y Raspao” will be presented as a space of opinion and information broadcast through the 22 stations that are part of the Fe y Alegria radio network and that will talk about the ALE.

Art and multimedia exhibition “Other Readings of the World: Perspectives of Youth and Adults”

On March 26, it will be the time to know the works registered in the multimedia exhibition “Other readings of the world”. The call for participation in the exhibition was launched on September 8, 2020 in the framework of the celebration of the International Literacy Day, seeking to provide a space for the presentation of experiences that are developed in this field of education and that highlight, through artistic expressions, the importance of ALE as a fundamental human right, its transformative potential and for the promotion of human rights and a dignified life.

On March 26, starting at 11:00 a.m. (Brazilian time), a virtual event will launch the website of the multimedia exhibition, where all the works submitted for the initiative will be presented, from different countries and experiences of ALE in Latin America and the Caribbean, in various formats: photos, documentaries, songs, videos, etc.

The launching, which will have the participation of the people registered to the exhibition, will have artistic exhibitions, and will be transmitted live through CLADE’s Facebook (@redclade) and Youtube (@clade).

>> Registration is now opened here.

Radio programs

A few hours before the launching of the “Other Readings of the World” Exhibition, at 9:00 a.m. (Brazilian time), a radio program of analysis of the current ALE situation will be presented with the participation of the audience and experts in this field of education. This program will have broadcast by the 22 radio stations that make up the Fe y Alegria radio network.

On the same day (March 26), at 18:00 (Brazilian time), it will be presented the radio program Contacto Sur Vespertino, a continental news program produced by ALER’s Continental Information Network (RIC), that is present in 19 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Colombian ALE experiences

On March 27th, starting at 9:00 a.m. (Colombia time), the Colombian Coalition for the Right to Education (CCDE) will present a live about ALE experiences from 6 regions of Colombia. In the event, participants of the experiences will tell about the violations and challenges they have had to face in the struggle for ALE as a human right in the context of the pandemic.

Access link through the Meet platform: https://meet.google.com/pjv-ksrm-ben

The event will be broadcasted through CCDE’s Facebook.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Action to End the Education Financing Crisis

February 12, 2021Article published in ALAI’s magazine No. 551: Derecho Humano a la Educación: horizontes y sentidos en la post pandemia 10/12/2020

1. Introduction

The right to education has been strongly asserted and embedded in human rights treaties for decades. Global leaders have also made bold political commitments to Education For All (EFA) first in Jomtien in 1990,i reiterated in Dakar in 2000 and reformulated as Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 in Incheon in 2015.ii But the right to education is routinely violated, with over 61 million primary-aged children out of school, a further 60 million out of lower secondary schooliii and an alarming 250 million children estimated to be in school but failing to learn. This article argues that the root cause of that failure is that grand commitments and declarations have not been matched by financial resources. Indeed, many of these commitments have been made during the decades when neoliberal economic thinking has been in the ascendancy, enforced around the world by the IMF and World Bank, whether through their loan conditions or coercive policy advice. Indeed, public education systems in most countries have been chronically underfunded for forty years.

The scale of the education financing crisis is being laid bare and exacerbated by Covid-19. At the height of the pandemic 1.5 billion children were forced out of school and it is unclear how many of them will be able to safely return. It is likely that millions of girls will not return to school owing to early pregnancy, early marriage or gender-based violence. It is equally likely that children who do return will find their schools with even greater resource shortages than ever. UNESCO estimates at least $210 billion will be cut from education budgets next year simply owing to declines in GDP. Pressure on governments to reallocate scarce resources to health might cut a further 5% from education budgets amounting to a total loss of $337 billion in education spending. Education systems that have already been underfunded for generations, may well face their most severe financing crisis in the next three years.

Thankfully, this bleak scenario is not a certainty. The Covid crisis could instead mark a turning point, with a renewed commitment to expanded financing of public education and other essential services. The solutions are clear but whether they are adopted depends on mobilising sufficient political will to seize this moment.

2. Action on Debt

An immediate first step has to involve action on debt. There was a new debt crisis emerging well before Covid came along. An increasing number of countries have been spending more on debt servicing than on education or on health. ActionAid’s research with the Jubilee Debt Campaign, published in April 2020, studied 60 countries, finding that the 30 countries with the highest debt servicing (over 12% of their national budget) had cut spending on public services by 6% in recent years. In contrast, those countries with debt servicing under 12% of their budgets, increased public spending by 14%. The link could not be clearer.

The latest Global Sovereign Debt Monitor has determined that 122 of 154 countries analysed should be considered “critically indebted.”iv According to UNCTAD, in 2020 and 2021 alone developing countries will be forced to hand over up to $1 trillion in external debt payments, money that is desperately needed for education and other frontline services. In the light of Covid various efforts have been made by the G20 and others to suspend debt payments for low income countries. This acknowledges the problem but fails to offer a viable solution as it does not reach all the countries needing help, does not address all the debt that they owe (including to private banks and China) and crucially only suspends payments for a short period. There is now a growing demand for full debt cancellation. This would have a transformative effect because it would give countries instant access to revenue that is already in their treasuries, enabling them to use that for a comprehensive response to Covid. Rather than paying back old debts, countries could spend their revenue on health, education and social protection.

In the longer term there is also a case for a new debt compact – between creditors and debtors – to ensure that all new loans are taken out based on a clear and transparent process, with proper democratic oversight. Loans can play an important role in enabling countries to invest in their development, but no country should ever find itself having to sacrifice crucial development goals I order to pay back old debts.

3. Action on Tax

Most education advocates have long focused on the share of the national budget spent on education – using the benchmark of 20% as an indicator of good practice. However, a fair share of a small pie is a small amount. By focusing almost exclusively on the share of the budget, education advocates have failed to pay sufficient attention to the overall size of government budgets – which is determined more than anything else by tax revenue.

Currently, tax revenues in low- and middle-income countries fall short of what is needed to guarantee universal quality public services. The average tax-to-GDP ratio in OECD countries is 33% of GDP in taxation with Scandinavian countries often having a ratio of over 40%. Lower middle-income countries average about 24% and low-income countries have an average tax to GDP ratio of just 16%. The countries with the lowest tax to GDP ratios – Pakistan and Nigeria – are also home to the largest numbers of out-of-school children. This is not purse coincidence. If a government does not collect sufficient tax revenue it is like a ‘regalian state’ (Thomas Piketty’s term), having the ceremonial appearance of a state but not in a position to deliver on its obligations to be a ‘social state’.

The IMF estimates that most countries could raise their tax-to GDP ratio by 5% in the coming years, so that the average low income country could rise from 16% to 21% – putting them in a position to dramatically increase social spending. ActionAid’s research showed that such increases could be delivered through Progressive Tax reforms ensuring that those who have more, pay more. This could be achieved through action on harmful tax incentives (through which countries lose $138 billion a year), aggressive tax avoidance (through which countries loose $500billion a year) , property, land and wealth taxes, carbon taxes, corporate income tax and digital taxes.

One of the great advantages of focus on tax reform is that this enables education advocates to find common ground with health activists, water and sanitation or social protection advocates. If we focus only on the share of the budget for education we are in competition with other sectors, but focusing on the size of the overall budget makes us allies. The table below shows what a 5% increase in tax to GDP ratio would mean for public services in a selection of countries:

| Country | Extra revenue in 2023 with 5% increase (compared to 2017) |

Could double budgets from current levels across social sectors… | …and still be left with |

| Afghanistan | $ 1.5bn | Education, health and social protection | $371m |

| Bangladesh | $32bn | Education, health and social protection | $ 17bn |

| Benin | $1.3bn | Education, health, social protection &WASH | $556m |

| Burkina Faso | $1.8bn | Education and health | $410m |

| Central African Rep | $172m | Education, health and WASH | $70m |

| Colombia | $30.8bn | Education, health and social protection | $3m |

| Congo, Rep | $1.9bn | Education, health and social protection | $1m |

| DRC | $8.2bn | Education, health, social protection &WASH | $6m |

| Ecuador | $6.3bn | Educationπ | $963m |

| Ethiopia | $11.6bn | Education, health and WASH | $5.89bn |

| Gambia, The | $156m | Education and health | $19.9m |

| Ghana | $7.8bn | Education, health, social protection & WASH | $3bn |

| Guatemala | $6.2bn | Education, health and WASH | $2.7m |

| Jamaica | $1.2bn | Health, social protection and WASH | $218m |

| Jordan | $3.2bn | Education, health and WASH | $2.8m |

| Kenya

|

$10bn | Education, health, social protection & WASH | $3.8m |

| Lesotho | $283m | Education∑ | $62m |

| Madagascar | $1.2bn | Education, health, social protection & WASH | $547.4m |

| Malawi | $732m | Education, health, and social protection | $97.6m |

| Mali | $1.8bn | Education, health, social protection & WASH | $620m |

| Mozambique | $1.3bn | Education and health | $0Ω |

| Nepal | $4.4bn | Education, health, and social protection | $2.3bn |

| Niger | $979m | Education, health, social protection & WASH | $121.6m |

| Rwanda | $1.3bn | Education, health, social protection &WASH | $697.5m |

| Senegal | $7.6bn | Education, health, social protection & WASH | $5bn |

| Sierra Leone | $380m | Education, health, social protection & WASH | $56.2m |

| South Africa | $27.9bn | Education | $3.5bn |

| Tanzania | $6.4bn | Education, health, social protection & WASH | $3.3m |

| Togo | $598mn | Education, health and WASH | $201.5m |

| Uganda | $3.1bn | Education, health, social protection & WASH | $1.5bn |

| Zambia |

$6.2bn |

Education, health, social protection &WASH | $3.7bn |

From https://actionaid.org/publications/2020/who-cares-future-finance-gender-responsive-public-services

ActionAid’s most recent research in this area looked at the amount of revenue that could be raise from just 3 big tech companies. If simple global reforms were made a selection of 20 countries could raise $2.8 billion between them from Facebook, Microsoft and Google. That could pay for 879,000 new teachers – who between them could transform education in each of the countries

4. Action on Austerity and Public Sector Wage Bills

Reducing debt servicing and expanding tax revenues could transform the resources available for education and other public services. But not in you are not allowed to spend the revenue you raise owing to coercive policy advice and loan conditions from the IMF which insist on austerity. In ActionAid’s 2020 report Who Cares for the Future: finance gender-responsive public services! one of the most startling statistics revealed that in 78% of low-income countries1, the IMF had advised countries to cut or freeze public sector wage bills in the previous three years. This has a particularly devastating impact on education as teachers are the largest groups on most public sector wage bills – so you cannot realistically recruit more teachers or pay teachers more if you have an overall limit. So, despite desperate shortages of teachers in many countries, Ministries of Finance have their hands tied by the IMF. This directly impacts any attempt to increase overall spending on education as teachers are often 90% of the education budget.

Revisiting this research six months later, in October 2020, the policy briefing The Pandemic and the Public Sector showed that although the IMF was being apparently generous in giving out emergency loans and allowing increase in health spending, they were also forecasting a rapid return to ‘fiscal consolidation’ – which is the IMF term for austerity. Indeed, most countries receiving emergency loans for Covid health responses were required to make clear commitments to revert to austerity within the coming year.

The root cause of the problem is that the IMF continues to see public sector wage spending as a problem rather than a solution. Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the fact, that the IMF does not consider the wages of public employees working in public services or other “pro-development” pursuits to be development spending; that designation is reserved for infrastructure such as schools and books for education, or hospitals, lab equipment and medication for health. If the significance of trained, quality workers for those areas were so recognized, it would be subject to “social spending floors,” which the IMF should, by its own guidelines, not recommend freezing or cutting.

Our latest research reinforces the case for a comprehensive evaluation of the IMF’s approach to public sector workers and public sector wage bills. There is a strong case for arguing that Covid-19 is the right moment for a fundamental re-think by the IMF, the time to move away from past policies, norms and practices which have left so many countries so ill-prepared for this health and economic crisis. Recognising that we are also facing a climate crisis increases the pressure for change – reframing how development is understood and moving beyond the narrow measure of GDP growth to factor in progress on human rights and development goals as integral to any economic measurement. And if the IMF does not embrace change then it is time for citizens everywhere to pressure their governments and international institutions to resist neoliberal dogma and adopt social and economic policies that value and care for both people and the planet.

5. Action on Increasing 4Ss

Whenever we argue for action on tax and debt and austerity a common response is that there is no point giving more money to governments because they can’t be trusted. Corruption is endemic and the money won’t end up improving public services in practice. Of course, we need to take this challenge seriously. There is corruption and mis-use of public resources (even though the bigger scandals are often in the private sector). We cannot just argue for more money for public education without a credible framework for how it should be spent. That is the logic behind the 4 S framework – which does not translate so easily into Spanish! This concerns the size of the budget overall, the share spent on education, the sensitivity of allocations and the scrutiny of spending in practice:

Increasing the share of the budget to education – as referenced above there is a well-established benchmark calling for governments to spend 20% of budgets on education. Tracking what share a government spends is a critical part of the bigger picture – but not enough on its own.

Increasing the overall size of government budgets – as outlined this is determined mostly by the tax revenue collected. However, it is also influenced by the macro-economic policies followed and by the level of debt

Increasing the sensitivity of the budget to policy priorities – some governments invest a disproportionate percentage of their education budget to benefit a small (but powerful and vocal) elite who access higher education. A more progressive and sensitive approach involves targeting spending to re-dress disadvantage. Pasi Sahlberg from Harvard University shows that countries who invest sensitively to make their education systems more equitable make significant progress in improving overall learning achievement.

Increasing the scrutiny of the budget – perhaps most important of all is that we need to ensure that there is independent scrutiny of education budgets. If people are not confident that budgets allocated will be properly spent it is hard to advocate for more resources. There are many positive examples of national and local budget tracking, of community audit groups tracking school budgets and of budgets being posted on school walls to ensure full transparency. These are crucial for ensuring that governments are held to account by their own citizens (rather than feeling accountable to external donors).

6. A Concluding Call to Action

In September 2020, 190 organisations signed a Call to Action on Domestic Financing of Education post-covid which touched on many of the key points raised in this article. The focus on domestic financing is key – as 97% of revenue for education is raised domestically (see The Learning Generation, Education Commission report). Aid and loans are relatively marginal – but they can make a difference when they incentivise or leverage deeper domestic commitment. Rich countries should play their part and reversing the recent decline in aid is important. But that aid should not come with conditions driven by donor countries. They should support the strengthening of public education systems based on national priorities set by national governments in consultation with national civil society. Sadly the aid effectiveness agenda is in decline with donor countries now more concerned to protect and advance their own trade and security interests. In this context, large increases in aid seem highly unlikely, though we can hope to defend and even increase the funding for some key actors who still seek to harmonise efforts, such as the Global Partnership for Education. Beyond that the call to the international community might more usefully focus on calls for debt cancellation, for changes to global tax rules and for ending the neoliberal obsession with austerity that has done so much to damage education systems around the world. Raising more funds from the international community always seems tempting as a way to make things better – but the real challenge is to stop the international system from continuing to make matters worse.

– David Archer, Head of Public Services, ActionAid International – david.archer@actionaid.org

1 In a review of IMF country documents for 2019, we found that of 23 low income countries (covering all the LICs with sufficient data available), seven (30%) expected to cut wage bills, 11 (48%) were freezing wage bills. Only five (22%) planned to increase wage bills.

i UNESCO, World Declaration on Education for All, Jomtien, Thailand (1990), adopted by the World Conference on Education for All, Jomtien, on 9 March 1990, https://bice.org/app/uploads/2014/10/unesco_world_declaration_on_educati….

ii UNESCO, Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning, UNESCO Doc. ED-2016/WS/28, 2016, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656

iii UNESCO, GEM Report 2016, http://uis.unesco.org/en/news/263-million-children-and-youth-are-out-school. The impact of COVID-19 on school attendance is discussed below.

iv Jubilee Germany/Erlassjahr, Global Sovereign Debt Monitor 2019, p. 4. https://erlassjahr.de/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Global-Sovereign-Debt-Monitor-2019.pdf.

The Assembly “Towards a global agenda: the human right to education from the movements” took place at the World Social Forum 2021.

February 1, 2021With the participation of a hundred delegates from organizations that converge around education as a human right, the self-organized assembly “Towards a global agenda: the human right to education from the movements” was held this Saturday (30) in the framework of the World Social Forum (WSF) 2021.

The activity was organized by the Latin American Campaign for the Right to Education (CLADE), the Council for Popular Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (CEAAL), the Pressenza Agency, the Espacio sin Fronteras Network, the Global March against Child Labour, the Global/Local Network for Quality Education, the Popular Education Network of Women (REPEM), the World Organization for Early Childhood Education (Omep) and Fe y Alegría.

Opening the dialogue, Grant Kasowanjete, Global Coordinator of the Global Campaign for Education, highlighted the need to ensure increased funding for public education in the countries of the global South as one of the main challenges to realizing the human right to education.

She pointed out that “for every dollar of aid that arrives from the global North, ten dollars are taken away through foreign debt and other mechanisms”, which erodes public coffers and underfunds the system, since 90% of education budgets come from own resources.

Nelsy Lizarazo, from the general coordination of CLADE, emphasized the deepening as result of the pandemic, of pre-existing inequality gaps and a refinement of stratification and exclusion from the educational pathway in social sectors lacking support, connectivity or adequate equipment, highlighting rural populations, migrants, indigenous people and people with disabilities, among others.

At the same time, she indicated how governments have handed over millions of dollars and data to corporations, information that will feed the already enormous business of these technology multinationals. She also added that the emergency has meant a greater precariousness of the teaching condition with budget reductions, salary reductions, a heavier workload, to which is added the psychological pressure produced by the effort of educators to respond to and overcome the difficulties posed by the technological and pedagogical challenge of distance education.

On the basis of these characterizations, the question of the learning, strengths and challenges identified in this course was launched as a trigger.

In a first round of interventions, key aspects such as the lack of infrastructure and the need for community technological development independent of large corporate platforms, the damage caused by the exclusion of millions of children from the educational process or the dysfunctionality of homogeneous educational planning in the face of the complexity of diverse realities were pointed out.

Among the lessons learned, the imaginative capacity of the educators who managed to overcome adverse conditions, the propensity for knowledge of children beyond the institutional framework, the importance of dialogue and joint work between school, parents and community, the role of community education together with the favorable impact of progressive political projects in the face of the failure of the neoliberal system were valued.

The assembly continued its collective reflection on the priority agenda of the regions and what is common to these agendas.

In a fluid and propositional dialogue, the participants indicated that the struggle must lead first and foremost, in the face of the prevailing violence in different territories, to guaranteeing the right to life. Likewise, to overcome inequality at educational levels within the social system, to offer safe educational spaces, free of aggression and abuse for girls and boys, and to strengthen a new non-predatory social relationship.

The need to promote a political-pedagogical revolution in the face of neoliberal agendas was also pointed out, as well as the need to strengthen intergenerational dialogue, especially in relation to older adults and the importance of implementing Comprehensive Sex Education as a mechanism to overcome sexual violence against girls, adolescents and women in general.

On the other hand, global priorities included the struggle to ensure that the right to education is not minimized, the defense and strengthening of the public system and counteracting the fallacy that private systems are better, overcoming inequality and discrimination in education, and guaranteeing adequate funding for education from a human rights perspective.

When analyzing possible cross-cutting themes for common action, the indivisibility of human rights was emphasized and, consequently, it was proposed to promote broad alliances by interweaving struggles with the agendas of other rights while contributing to strengthening social organization and mobilization. The importance of continuing to generate knowledge by connecting it with messages and campaigns that mobilise demands was highlighted.

In the same way, a suggestion was made in the debate for a greater exchange on the modalities used to make good practices visible and to achieve effective impact in relation to the demands put forward.

Among the proposals for joint action, the creation of an observatory, the promotion of liberating education in the presence of Paulo Freire’s centenary, the opening of spaces for the expression of the new generations and the idea of Good Living were suggested. Political action is needed to rethink education in terms of feminism and socio-economic equity, and to articulate the forces to overcome not only the physical but also the mental illness from which humanity suffers.

Finally, the Assembly approved a text to be proposed and included in the final declaration of the World Social Forum 2021.

“In the framework of this WSF 2021, we join the agenda of transformation at the global level, articulated to the various fields of social struggle and rights, recognizing the catalytic role of education. The pandemic highlighted the historical inequalities within and outside education systems, affecting women, girls, people with disabilities, refugees and migrants, indigenous communities, rural populations, among others. It also highlighted the digital divide and government responses to it, as well as the need to build a digital sovereignty strategy.

Through strengthened public education systems, it is necessary to resist the threats of fiscal austerity policies, national indebtedness and cuts in education funding, as well as the multiple trends of privatization. From early childhood through to youth and guaranteeing adult education, it is essential, in the post-pandemic period, to rethink the meaning and purpose of education, in the search for the rights of peoples and overcoming patriarchy. A heterogeneous and intercultural model, transformative and inclusive; based on dialogue and safe for communities; valuing their knowledge and local knowledge, as well as collaboration in solidarity and commitment to the protection of life”.

Video:

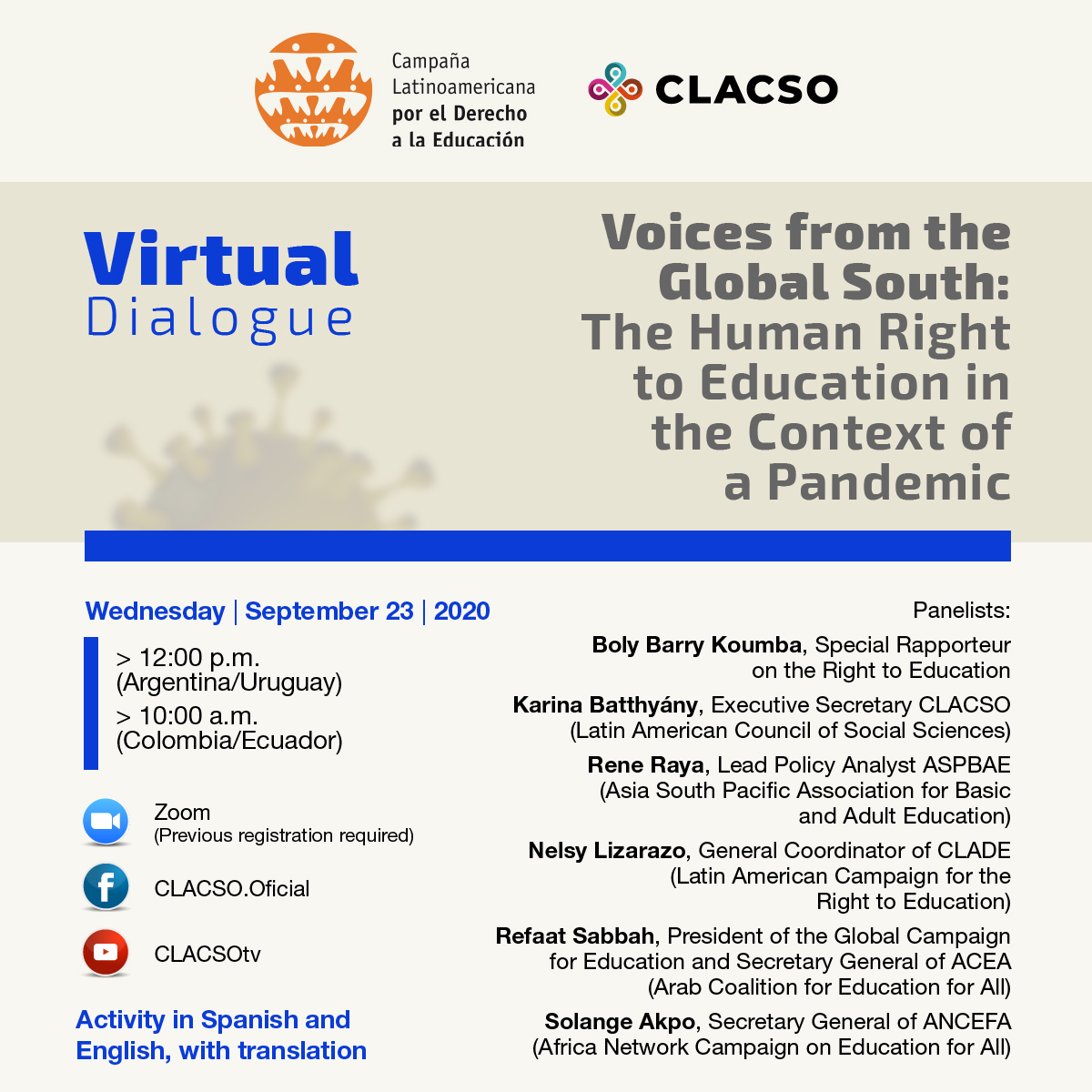

CLADE and CLACSO are promoting a webinar on the Right to Education from a Global South perspective

September 15, 2020 On September 23, at 12:00 p.m. (GMT-3), the Latin American Campaign for the Right to Education (CLADE, by its Spanish acronym) and the Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO, by its Spanish acronym) will organize a virtual dialogue “Voices from the Global South: The Human Right to Education in the Context of a Pandemic.”

On September 23, at 12:00 p.m. (GMT-3), the Latin American Campaign for the Right to Education (CLADE, by its Spanish acronym) and the Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO, by its Spanish acronym) will organize a virtual dialogue “Voices from the Global South: The Human Right to Education in the Context of a Pandemic.”

The objective of this gathering is to analyze, reflect and debate on the human right to education in the context of a pandemic, and from a Global South perspective. United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur for the Right to Education, Boly Barry Koumba will participate in this event. Joining the Special Rapporteur will be CLACSO Executive Secretary, Karina Batthyány; CLADE General Coordinator, Nelsy Lizarazo; the President of the Global Campaign for Education (GCE) and Secretary General of the Arab Coalition for Education for All, Refaat Sabbah; the Lead Policy Analyst of the Asian South Pacific Association for Basic and Adult Education (ASPBAE), Rene Raya; and the Secretary General of the African Network Campaign on Education for All (ANCEFA), Solange Akpo.

The activity is open, free and will be broadcasted through CLACSO Facebook page, Youtube and Zoom. The webinar will be conducted with Spanish-English simultaneous translation. Previous registration here is required for Zoom participation.

Pan-American Congress analyzes the advances and challenges for achieving the rights of boys, girls and adolescents

May 20, 2020Overcoming discrimination and violence, the right to play, art and recreation, gender equality and the right to comprehensive sexuality education and to participate in the debates on public policies affecting them: these were some of the demands shared by boys, girls, adolescents and youths during the 22nd Pan-American Child and Adolescent Congress and the Third Pan-American Child Forum that were held from Oct. 29-31 in Cartagena (Colombia).

(more…)

“There is a lack of specific indications on how to achieve the human right to early childhood education”

May 15, 2020¨The Right to Early Childhood Care and Education in Latin America and the Caribbean in the Context of Global, Environmental and Social Challenges.¨ was the title of a virtual panel carried out by the Latin American Campaign for the Right to Education (CLADE), in partnership with World Organization for Early Childhood Education (OMEP), and EDUCO, within the 64th Annual Conference of the Comparative & International Education Society (CIES).

In order to analyze the situation of the right to early childhood care and education in Latin America and the Caribbean, the event was held on March 25th, and included the participation of: Peter Moss, Professor at the Institute of Education from the University of London, and expert with a recognized track record in the field of early childhood education; Mercedes Mayol Lassalle, World President of OMEP; Madeleine Zúñiga, coordinator of the Peruvian Campaign for the Right to Education (CPDE); Vernor Muñoz, director of Policy and Advocacy of the Global Campaign for Education (CME); and Camilla Croso, general coordinator of CLADE, who participated as moderator.

Below you can read the reflections and perspectives that were highlighted in the panel:

Another kind of policies for Early Childhood Care and Education are possible

According to Peter Moss, the global hegemony of neoliberalism and the fact that early childhood care and education (ECCE) have become a political priority worldwide, have led to the consideration of this stage of life as an efficient means of maximizing “human capital”.

“This can be seen in particular in a dominant narrative that has driven national and global policy making in ECCE, a narrative that is instrumental and economistic in rationality and adopts technical practice as first practice: it is a narrative that I have termed ¨the story of quality and high returns ”, he stressed. ¨ In this way that the story goes, early childhood care and education will ensure individual and national success in an increasingly cutthroat global market place, and everyone lives happily ever after¨, he added.

“Those of us in the early childhood field need to be able to understand and relate to transformative ideas emerging in other fields including economy, democracy and environment.”

According to the researcher, this instrumental and economistic perspective is not only present in early childhood care and education, but it cuts across the entire educational field. ¨We also have to take into account the existence of a model of economic development that seeks to reduce the very diverse social and cultural phenomenon such as education to issues of mercantile efficiency or economic growth¨, he pointed out.

He also added that the construction of another perspective of education and care in early childhood, one that is not oriented towards the search of high returns, must be based on democratic political decisions for education, in conjunction with other policies. “It should be connected, entangled with, a larger process involving education as a whole, and indeed the struggle for a future that is built on democracy, social justice, solidarity and sustainability”.

He also affirmed that professionals and thinkers in the field of early childhood should be able to understand and relate to transformative ideas that arise from other fields, beyond education, including economy, democracy and the environment. ¨ While those working on those broad subjects need to be aware of what early childhood, and indeed all education, could contribute to them. ¨

Privilege versus Human Right

¨ Despite the powerful definition of children as holders of rights, enshrined in United Nations` Convention of the Rights of the Child, and the valuable guidelines on the Right to Education, there still is a lack of specific indications on how the human right to education is achieved in early childhood.¨ commented Mercedes Mayol Lassalle, during her intervention.

“Despite the expansion in enrollment, inequality in terms of access persists because households with high economic level are 30% points above the access values of 5 year old children from the poorest households.”

For OMEP President, there are important challenges in terms of the effective implementation of comprehensive and intersectoral approaches to the rights of boys and girls in Latin America and the Caribbean. Inequality in terms of access to education is another challenge in the region, which is confirmed by, for example, the enormous gap in access that exists between children over three years of age and children from birth to three years of age. For this last age group State coverage is very restricted, forcing families to pay for these services.

“Despite the expansion in enrollment, inequality in terms of access persists because households with low economic level are 30% points above the access values of 5 year old children from the poorest households.” she added.

During her presentation, Mercedes analyzed the conclusions of CLADE´s research: ¨The Right to Early Childhood Care and Education: Perspectives from Latin America and the Caribbean¨.

Another important aspect that she highlighted is that the offer of free and compulsory early childhood education is still limited in the region. “International agreements, particularly the Education 2030 Agenda establishes compulsory education at least for 1 year before and attending primary school, and in many countries of the region it has been extended to two or three years before primary school.¨ explained Mercedes Lassalle.

She concluded by saying that, unfortunately, in the region, ¨Early Childhood Care and Education is a privilege for some children, more than a human right for all, particularly from birth up to 3 years of age¨.

Challenges of Early Childhood Care and Education in Peru

In her presentation, Madeleine Zúñiga took us on a historical tour on public policies for early childhood care and education in Peru, from the experience of the “Wawa Wasi” Centers (House of Children, in Quechua), established during the last years of the decade of the 1960s in the southern region of the Peruvian Andes, to the promulgation of the General Education Law Nº19326 in1972, and up to the current challenges they are facing.

“Diversity should not be the problem, but it is the source of great social inequities, that result from the shameful discrimination still ingrained in our society. ¨

For the coordinator of the Peruvian Campaign, the first and perhaps most difficult of the current challenges is the need to overcome the fragmentation of early childhood education by age range, this due to the fact that the responsibility for the administering of policies aimed at early childhood is distributed among three Ministries: Ministry of Development and Social Inclusion (MIDIS), Ministry of Education (MINEDU) and Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations (MIMPV), according to the different ages and social needs of children in the country.

The complex diversity of the population in terms of socioeconomic levels, geographic location, cultural and ethnolinguistic diversity, as well as inclusion and equity, represents another permanent challenge. “Diversity should not be the problem, but it is the source of great social inequities, that result from the shameful discrimination still ingrained in our society. These inequities are easy to identify not only in access to services but also in the quality of the services, which leads us to affirm that education continues to be a privilege rather than a universal human right,” she affirmed.The educator and activist also emphasized on the need to improve the quality of all public early childhood care and education and preschool educational programs, as well as to ensure data and evaluation on the quality and relevance of these policies, together with adequate and contextualized teacher training for this stage of life.

¨For them to achieve an optimal performance the initial training of teachers under a human rights approach is urgent. Early childhood deserves attention from professionals whose performance is based on the valuable and meaningful articles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. (…) Training will give teachers the skills to make the educational experience an experience of democracy, solidarity, and learning to live with others” she said.

Educational systems that do not correspond to realities

At the end of the event, Vernor Muñoz participated with his own observations and analyzed the interventions of the panelists. According to CME Director of Policy and Advocacy, the utilitarian vision of early childhood education, and education in general, has been widely criticized by various human rights mechanisms and organizations.

¨It was Katarina Tomasevski who brought back the attention about 20 years ago on how some economists define education as a production of human capital, and classify all human right dimensions just as externalities. And today, 20 years later, we still see how the World Bank and many development agencies still consider people as human capital instead of subjects of rights¨, Muñoz pointed out.

“We can see that the best interest of the child is well defined by the Human Rights international instruments. But in terms of practical application it is always under the interpretation of those who have the power to decide. ¨

For the activist and former UN relator on the Right to Education, the utilitarian and authoritarian approach to education also reveals that current educational systems do not correspond to people’s realities, not even in the case of the few children who manage to enter the educational system. “We can see that the best interest of the child is well defined by the Human Rights international instruments. But in terms of practical application it is always under the interpretation of those who have the power to decide. So again, under a restrictive and utilitarian view the best interest of the child is usually seen as the potential capacity to become a good consumer.” he concluded.

Questions from the audience

After the virtual dialogue, Peter Moss answered two questions from the audience that could not be discussed during the debate. Read his answers:

Early childhood education from 0 to 3 years is a challenge. There are good experiences found in many countries. What is the view on family education?

Peter Moss – I don’t know the background to this question or the conditions of Latin America and the Caribbean countries, So, I can only say what interests me in a UK and, more broadly, a European context.

Much of my work concerns the development of parenting leaves, so parents can take time away from employment when they have a young child; it is very important that this is shared equally by both parents. So I think the aim should be to provide at least 12 months well paid leave, with at least 4 months for fathers only and 4 months for mothers only.

“We should think of families participating in learning communities, which also provide opportunities for building intergenerational solidarities, practicing participatory democracy and respecting diversity”

After this, children should have access, as of right, to good early childhood education. I also think this education should be in multi-purpose, community-based centres – we call them ‘Children’s Centres’ in England – providing a wide range of services for children, their carers and the local community, and based on values of equality, democracy and solidarity: this is the centre as a shared resource, a public space and place of encounter for citizens.

Rather than educating families, we should think of families participating in learning communities, which also provide opportunities for building intergenerational solidarities, practicing participatory democracy and respecting diversity.

Could you please mention some issues that are relevant for researchers’ groups and universities in Early Childhood Care and Education? Some “new” gaps or topics that we have not taken into account?

Peter Moss – Again, I can only say what interests me in a UK and, more broadly, a European context; others would have very different answers.

First, I think there is a need to develop systems of participatory assessment and evaluation that can recognise and value complexity and diversity., with respect to both children and early childhood centres.

Second, I think there is a need for more work on gender in early childhood education, and especially to better understand the continuing highly gendered nature of early childhood workforces and to propose how this might be reformed.

Third, I think there is a need for research on how democracy can be practiced and deepened in early childhood education, to include participation by children, parents and workers.

Last, I think we need to develop more comparative research (between countries), looking both at structures and cultures of early childhood education, and focusing on elaborating and understanding differences.

Below you can find the panel that was broadcasted in English, available with subtitles in Portuguese and Spanish.

Access the dialogue with subtitles here

CIES 2020: None of the countries from Latin America and the Caribbean explicitly prohibit profit in education

May 12, 2020Chile, Haiti and Paraguay are three countries from Latin America and the Caribbean where legislations clearly lead to the generation of profit and privatization in and from education. At the same time, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Honduras, Mexico and Peru have legislations that allow for profit in education. These are some preliminary findings of the study on “Profit and education within legal frameworks in Latin America and the Caribbean” that the Latin American Campaign for the Right to Education (CLADE) is conducting.

Some of the conclusions of the research were presented by Teise Garcia, from the Research and Study Group on Education Policy (GREPPE, by its Spanish acronym) from Brazil, during the virtual panel: “Marketization and Profit in and from Education: Global and Regional Perspectives in Latin America and the Caribbean”. The debate was held within the framework of CIES 2020 on April 15.

“We did not find a full prohibition that explicitly prevents public incentives to profit in any of the countries of the region that were analyzed in this study. Only Argentina is worth mentioning because bilateral and multilateral agreements related to profit generation are prohibited”, stated Teise García.

Apart from the researcher, the panel was attended by the following participants: David Archer from ActionAid International; and Cecilia Gómez from the Colombian Coalition for the Right to Education, (CCDE, by its Spanish acronym). Camilla Croso, General Coordinator of CLADE, and Toni Verger, from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, were in charge of the debate and moderation, respectively.

The objective of the panel, organized by CLADE, was to promote reflections and dialogue on education privatization and profit processes in the region, as well as their negative impact on the realization of education as a human right for all.

Lack of funding and creation of poverty

For David Archer, from ActionAid, the increase in education marketization and profit owes mainly to the lack of public funding for this right which is a problem that educators, activists and consultants should focus on.

Insufficient public education coverage, combined with a growing structural deficit in public education funding has paved the way for the emergence and consolidation of a for-profit private education market which seems to be increasingly the norm in the region”, he said.

He added that the reason for this lack of adequate funding for the right to education, in most cases, is the external debts of the countries and the absence of tax justice. “There is a new external debt crisis”. At this moment, there are 60 countries that allocate more than 12% of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to pay the external debt. This means that the payment of the debt exceeds the financing for education and health, which is absurd amidst the COVID-19 crisis that we are facing”, he pointed out.

According to Cecilia Gómez, lack of State funding for the realization of rights and, consequently, the privatization of public services, create poverty. “I think that this neoliberal model which in our countries results in privatization (of water, energy, education, etc.) creates extremely high poverty rates, impoverishment of people who are already poor and are now reaching misery levels”.

COVID-19: Guides on the education and protection of children and adolescents

April 9, 2020At this time of crisis, the National Campaign for the Right to Education (CNDE), a member of CLADE in Brazil, in alliance with the Cada Criança platform, has made available two guides aimed at families, schools, local social security agents and authorities so that they can guarantee the protection and education of children and adolescents.

“The goal is to offer verified and accessible information on how citizens linked to education can act, demand and work for the protection of all and in a collaborative way and also, by public authorities, guarantee the rights of girls and boys and adolescents in emergency situations” says CNDE.

Read below a summary of the guides in English or download here the complete document in Portuguese aimed at families and education professionals, and the guide for authorities here.